A systematic examination of the tumor and the tissue surrounding it—particularly normal cells in that tissue, called fibroblasts—has revealed a new treatment target that could potentially prevent the rapid dissemination and poor prognosis associated with high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC), a tumor type that primarily originates in the fallopian tubes or ovaries and spreads throughout the abdominal cavity.

High-grade serous carcinoma is the most common form of ovarian cancer and the most deadly. Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage when the disease has already spread. Five-year survival is around 50 percent.

“Until quite recently, scientists have focused on the tumor itself,” said the study’s senior author Ernst Lengyel, MD, Ph.D., professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago Medicine. “Everyone does.”

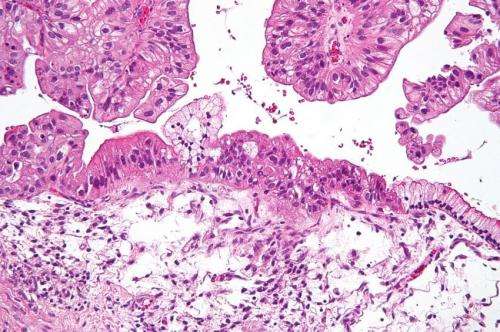

But given the lack of progress with that approach and the fact the tumors are complex organs comprised of different tumor-supporting cell types (stroma), “we thought it might be better to focus less on the cancer and more on the stroma, the supporting tissue that surrounds the cancer and enables its growth.”

In the May 1, 2019 issue of Nature, the researchers show that the stroma has a major impact on cancer cells. “In this case,” Lengyel said, “it makes them more malignant, more aggressive and more invasive. The stroma is often bigger than the cancer itself.”

In close collaboration with Fabian Coscia, Ph.D., and Matthias Mann, Ph.D., from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Munich and University of Copenhagen, the researchers profiled the expression of more than 5,000 proteins in both normal and cancerous tissues derived from minute amounts of patient biobank material.

“For the first time, we were able to distinguish the molecular changes in the cancer cells from the ones happening in the adjacent stroma throughout disease progression,” explained Coscia. “When we then got our data, we were fascinated to find that the metastatic stroma was characterized by a highly conserved protein signature, as opposed to the cancer cells.”

These metastatic changes were seen in all analyzed patients. The researchers are now trying to understand their functional role during metastasis with the goal of finding novel therapeutic targets.

In the process, they discovered a metabolic enzyme, nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT), that was highly expressed in the stroma surrounding metastatic cancer cells. They found that NNMT causes widespread gene expression changes in the tumor stroma, converting normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts that support and accelerate tumor growth. Stromal NNMT expression encouraged ovarian cancer progression and metastasis. It was associated with very poor patient outcomes.

The researchers are now using high-throughput screening to find novel ways to inhibit this enzyme. “One method looked promising,” said Mark Eckert, MD, research assistant professor in obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Chicago and first author of the study. “We have a backbone for several candidate inhibitors. We know our target, we know the structure, we know how to apply this and we have a sense of the direction. We are starting to understand how a normal fibroblast is converted into a cancer-associated fibroblast by this metabolic enzyme.”

They also found that inhibition of NNMT activity reduced or even reversed many of the tumor-promoting effects of cancer-associated fibroblasts. This suggests, they note, that the stroma should be explored as a new treatment target.

Coscia, co-first author on the manuscript and leader of the proteomics analysis, added that “this method may be used to discover other proteins that are important for metastasis and to identify early changes during disease development.”

“When we put it all together,” Lengyel said, “it gave us exciting results. We have linked high-end technology, including proteomics and metabolomics, to improve our understanding of the stroma.”

This article was published by Medical Xpress.