Blood-based metabolic signatures may predict whether women with ovarian or uterine cancer will respond well to platinum-based chemotherapy, according to a study by researchers in the Department of Gynecology at the Federal University of São Paulo’s Medical School (EPM-UNIFESP) in Brazil, in partnership with colleagues at the University of California Irvine (UCI) in the United States.

The study sample consisted of 50 women with ovarian and endometrial tumors who received surgery and first-line chemotherapy. The findings are published in Gynecologic Oncology.

“Our aim was to measure the metabolic signatures – molecules originating in the metabolism and present in the bloodstream – that could be associated with a specific illness or condition,” said lead author Paulo D’Amora, a member of the steering committee of EPM-UNIFESP’s Molecular Gynecology and Metabolomics Laboratory.

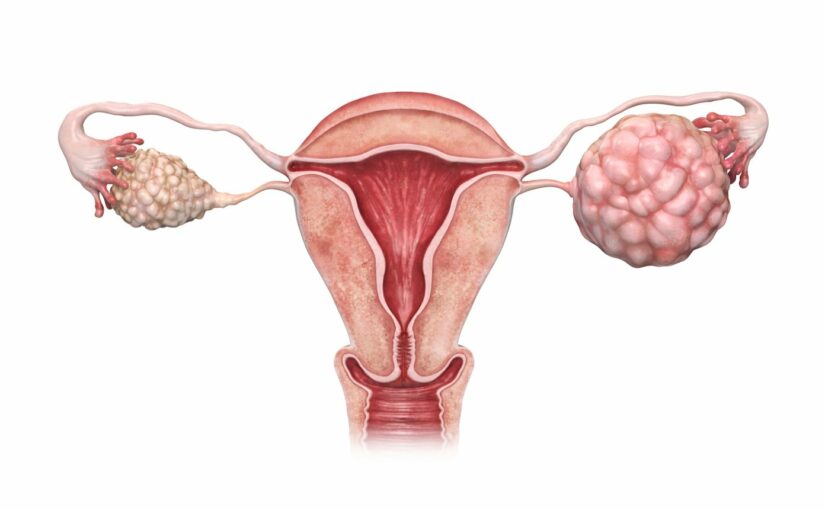

More than 117,000 new gynecologic cancers are diagnosed in the U.S. annually, with adenocarcinomas of the ovary and uterus being the most common. Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer, with 21,750 new diagnoses and 13,900 deaths annually. It’s followed closely by endometrial cancer with 65,620 new cases and 12,520 deaths.

Patients with advanced ovarian and endometrial cancers usually undergo some type of surgery and receive postoperative platinum-based chemotherapy, typically carboplatin plus paclitaxel. Over 80% of ovarian and 60% of endometrial cancer patients initially respond to platinum-based chemotherapy, but the majority relapse. That trend has spurred research into the cellular mechanisms of platinum resistance including drug uptake, neutralization by intracellular thiols, and DNA repair.

In this study, D’Amora explained, the researchers used mass spectrometry to analyze levels of the amino acids valine and phenylalanine (linked to immunity), and lipids such as the acylcarnitines, lysophosphatidylcholines, and sphingomyelins (associated with alterations that lead to stimulation of inflammatory pathways and energy expenditure).

“With the aid of a next-generation mass spectrometry system, we measured the ions emitted by the compounds of interest in the plasma samples collected from the patients,” D’Amora said. “Ions are accelerated and fragmented in the spectrometer. Each metabolite has a specific fragmentation pattern, a unique identity.”

The results pointed to the patients who were platinum-sensitive or platinum-resistant.

The study participants were divided into two groups: 38 platinum-sensitive patients (83% of the total), and eight platinum-resistant patients (17%). The spectrometry results were correlated with those of clinical and laboratory exams and, after a metabolomic analysis, led to information on the patients’ clinical response, such as disease-free survival, time to progression and overall survival.

The researchers began with these types of tumor because they are sensitive to chemotherapy with platinum-based drugs. They were able to identify patients with metabolic profiles associated with the best clinical response and prognosis, or with unfavorable profiles and a poor prognosis. They hope this information will help physicians personalize treatment and improve probability of a cure based on results of a blood test that looks for specific metabolic signatures.

“We’re working on ways of ensuring that the biomarkers and algorithms found in the study can achieve the validation levels required by regulators in Brazil and abroad so as to win accreditation for their use in laboratory medicine and clinical pathology. Once that happens, they can be used in clinical practice,” said D’Amora.

This article was published by Clinical Omics.