By: Susan Gubar

Six days after an unremarkable lumpectomy, I had rushed to the local hospital, not so much because of pain but out of concern. I had been eating and drinking as usual, but what was going in was not coming out.

I cursed my faulty plumbing — an operation for ovarian cancer had produced infections and then, in 2009, an ileostomy. I’m one of about half a million Americans whose body wastes are collected in disposable external pouches. And now the pouch was clean and empty, which was a problem.

Unfortunately, I had made the situation worse by forgetting to bring a book to the hospital with me. Within an hour, a nurse named Rachel came to my rescue with a thriller, “The Donor.” According to the flap, Frank M. Robinson’s hero awakens in a recovery room to discover that one of his kidneys has been harvested by a mysterious villain who will next time seize the poor guy’s heart. Sounded perfect.

Rachel’s book, a life preserver, saw me through 12 hours in the emergency room as well as most of the next day, which I spent in a hospital room. I was receiving “rest care”: nothing by mouth, an IV with saline to prevent dehydration. If my intestines did not start working, I would be transferred by ambulance to a major hospital in Indianapolis, an hour and a half away from Bloomington, where I live.

One doctor told me: “You have an 80 percent chance that the obstruction will right itself.”

It was a new experience to look down at the pouch plastered on my belly with alarm that it was clean. Daily since the ileostomy eight years ago, I have struggled with disgust: certainly not the prescribed or healthy response, but mine nonetheless. A bit of intestine — called a stoma — had been pulled out of my body and stitched to my stomach so stool could be evacuated.

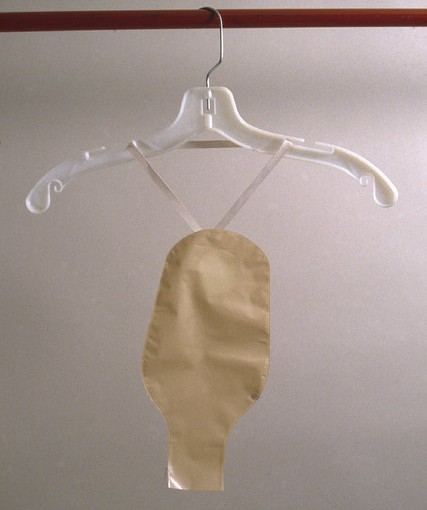

Until this stoppage, the productivity of the stoma had revolted me. Every few hours, the bag needed to be emptied. Every few days, I changed the apparatus that, glued to my body, collected waste. Like many others living with temporary or permanent colostomies, ileostomies and urostomies, I hid the pouch beneath my clothes, while I stressed over skin irritation, accidental leaks and mortification.

Was the pouch empty because of something I had ingested? People with ileostomies are warned against fibrous foods. Corn, cauliflower, mushrooms, cabbage, celery, beans, nuts and berries can cause blockages, so I am supposed to follow a diet low in roughage. At my last meal, I had eaten a sprinkling of parsley on a piece of cod, but surely not enough to clog the works.

The gruesome premise of the book I was reading, “The Donor” — of body parts excised from the living — made me wonder if medically engineered, artificial organs might create better solutions for various ostomies caused by a number of maladies: birth defects, injuries, inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease and gynecological, bladder or colorectal cancers. Quite a few “ostomates” manage to engage in a full range of activities, but I find it impossible to swim, take baths or exercise vigorously because of anxieties about the adhesive eroding under the pouch.

Around 7 p.m., my alimentary system started working again and I exulted at the prospect of going home.

Before my release the next day, an ostomy nurse arrived with a cart full of brochures and equipment.

“Supplies have changed since 2009,” she said, handing me samples of newly designed products. Too tired and fraught to attempt anything new there and then, I took her card, determined to consult her when my digestion had settled down. Maybe she could make my life easier, for in my experience ostomy nurses crowd the angelic throngs.

One week later, at a post-op consultation about my lumpectomy, the breast surgeon said she thought that even days after the procedure, remnants of anesthesia might have put my small intestines to sleep. “Could have happened to anyone,” she said. It dawned on me that the ostomy was no more or less gross than any other mode of evacuation.

These days, I’m grateful for little acts of kindness from gracious people who leaven the misery of hospitalization. Online I find a grisly medical thriller to send Rachel, along with the book she had lent me. Bolstered by her and the ostomy nurse, I seek, like the protagonist of “The Donor,” to keep hold of my heart.

“Secrecy and shame cannot be kind masters,” my cherished friend Mare says to remind me how many people, with and without cancer, must deal with physical impairments. Art also helps: Carol Chase Bjerke’s “Intimate Apparel” puts on display the usually hidden ostomy pouch as if it were a delicate piece of lingerie. It’s unnerving, but clarifying to see the concealed revealed.

To read this entire article, published online by The New York Times, click here to login to The Clearity Portal.