Researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have found a relationship between the genetics of tumors with germline BRCA1/2mutations—and whether the tumor retains the normal copy of the BRCA1/2 gene—and risk for primary resistance to a common chemotherapy that works by destroying cancer cells’ DNA. The team published their findings in a paper by Maxwell et al in Nature Communications.

Researchers estimate that 5% of breast cancers and 20% of ovarian cancers are attributable to germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

There are many reasons patients may be resistant to treatment: the immune system, the complex landscape of a tumor, or a patient’s own genes can all play a role. Without explicitly looking for it, the Penn team found another mechanism of resistance to a standard treatment for patients with BRCA-associated cancers. “Our primary question was not aimed at evaluating resistance to therapy, but we did end up there,” said senior author Katherine Nathanson, MD, Deputy Director of the Abramson Cancer Center and Director of Geneticsat the Basser Center for BRCA.

Her group evaluated the genetic profiles of 160 breast and ovarian cancers associated with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, in the largest study of these tumors to date. They were interested in determining what types of secondary, additional changes occur in primary BRCA1/2 germline mutation-associated cancers that might act in concert with mutant BRCA1 and BRCA2 to drive the cancers.

Study Findings

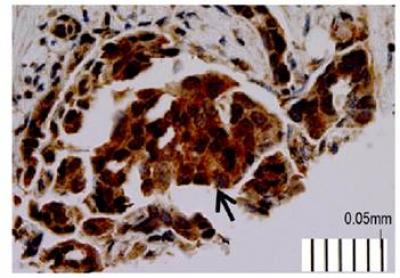

The team evaluated how frequently the nonmutated version of the gene lost its function in concert with the original BRCA1/2 germline mutation-associated cancers. This double-hit status is called “loss of heterozygosity,” or LOH, to signify that both versions of the normal BRCA gene have been hobbled.

Historically, it had been thought that all tumors associated with germline BRCA1/2 mutations experience LOH. The investigators were surprised to find that was not the case in a surprisingly large percentage of patients. In addition, they found that other genetic and clinical features of patients whose tumors did not undergo LOH (LOH–negative) were significantly different from those that did undergo LOH (LOH–positive).

Notably, they evaluated the overall survival of patients with ovarian tumors with and without loss of heterozygosity. LOH–negative status was associated with worse overall survival in ovarian cancer patients treated with platinum chemotherapy, with a median of 39 months compared to 71 months in the LOH–positive group who received the same treatment.

The researchers believe the patients with LOH–negative tumors (those with one working copy of BRCA1 or BRCA2 and the other copy carrying the germline mutation) had tumor cells that could still repair the chemotherapy-induced DNA damage in order to survive. In contrast, the investigators surmise that the LOH–positive group (with both gene copies disabled) responded better to the same therapy because their tumor cells died more readily.

“Identifying the LOH status of BRCA1/2 carriers may be useful to predict who might be at risk for primary resistance to DNA-damaging agents such as platinum, which has important implications for treatment of patients with these mutations,” said the study’s first author Kara N. Maxwell, MD, PhD, Instructor of Hematology/Oncology at Penn. “We only need to determine the LOH at a specific gene’s location, which is more cost-effective than sequencing a patient’s whole genome, for example, and compatible with standard testing.”

Dr. Nathanson surmised that knowing a person’s LOH status could guide treatment decisions. She suggests that certain drugs already in today’s cancer treatment arsenal will likely work for patients who are at risk for resistance due to their LOH genetics; however, it’s a matter of choosing the right one.

To read this article and more in The Clearity Portal, click here to login.