A new class of drugs could be a significant step forward in the treatment of ovarian cancer, one of the most lethal forms of the disease. The drugs, known as PARP inhibitors, are thought to help the body slow the disease’s progression by helping to prevent cancer cells from repairing themselves after chemotherapy treatment, thereby shrinking tumors and delaying relapses.

The drugs don’t work in everyone, and are thought to have the greatest effect in women with mutations of the BRCA genes, who represent about 15% of ovarian-cancer patients. But recent research, still ongoing, indicates that the drugs may benefit an additional 35% of patients with different genetic profiles.

“We’re not seeing cures, but we’re seeing patients benefit in a really major way,” says Dr. Robert Coleman, a gynecologic oncologist and PARP researcher at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “The question is, can we expand [the drugs] to more patients?”

An estimated 195,770 U.S. women live with ovarian cancer. Fewer than half of them are expected to be alive five years after being diagnosed. That compares with a five-year survival rate of 90% among breast-cancer patients and 67% among all cancer patients, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The low survival rates are partly due to a lack of an effective screening test, such as a mammogram for breast cancer, to detect the disease early when it is most susceptible to treatment.

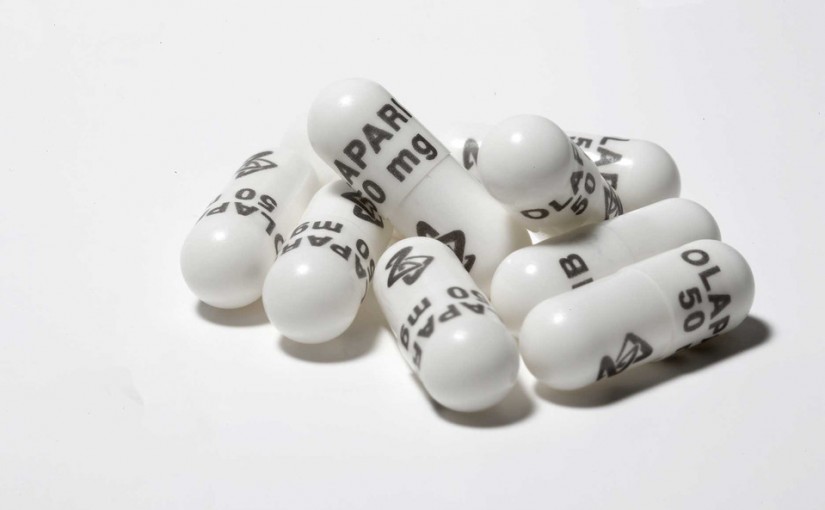

One PARP inhibitor pill is already on the market— AstraZeneca’s Lynparza—but it is approved for only a small share of patients, after other options have failed. Two new drugs in the class could be approved as soon as next year for many more patients following the release of encouraging clinical trial data this summer.

Some experts doubt that PARPs are a significant advance or worth their cost—Lynparza costs roughly $12,000 for a month’s supply. The main objection is that studies haven’t shown that patients actually live longer after taking a PARP than patients who don’t.

“The quality of data” backing PARP inhibitors “has been fairly weak and rather unimpressive,” says Vinay Prasad, an oncologist who studies clinical trial design.

Seana Roubinek, a computer analyst in Rockport, Maine, was diagnosed with ovarian cancer five years ago and began taking Lynparza in December after her disease returned for a second time. A recent CT scan showed that her tumors had shrunk by two-thirds and blood tests continue to show her tumor activity going down.

Ms. Roubinek, 48, says taking the Lynparza pills twice a day is more convenient and has fewer side effects than chemotherapies she has had in the past. The drug caused a drop in her red blood cells, which can cause anemia, but the problem was fixed after cutting her dose in half. Ms. Roubinek says her insurance pays most of the cost of the drug and AstraZeneca’s financial-assistance program covers her copay.

The way PARP inhibitors work is complex. The drugs help muzzle production of enzymes that play a role in helping DNA to repair itself. That can be effective in finishing off the destruction of cancer cells after they have been damaged by chemotherapy.

BRCA gene mutations also prevent DNA repair, which is why women with the mutations are at increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. But those mutations, when combined with PARP inhibitors, can later help fight cancer by working against the resurgence of tumor cells.

Recent research shows that other genetic variations may also block DNA repair, indicating that PARP inhibitors may benefit more women than those with BRCA mutations.

In June, Tesaro Inc. said BRCA patients taking its drug niraparib lived for a median of 21 months before their cancers relapsed in a late-stage study, nearly four times longer than the 5.5 months in patients taking placebos. But the drug also provided a benefit, albeit a smaller one, to patients without inherited BRCA mutations who tested positive for deficiencies in a DNA repair mechanism known as homologous recombination. Those patients lived a median of 12.9 months without their cancer progressing, compared with 3.8 months for patients taking placebo, Tesaro said.

Tesaro released the data in a press release; full-study data will be presented at an October medical meeting. The company plans to seek FDA approval later this year and is hoping to launch the drug in the U.S. by mid-2017.

This article was originally published online by The Wall Street Journal. Read the full article on The Clearity Portal by clicking here.