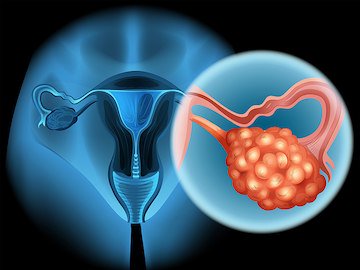

Women should not undergo screening for ovarian cancer if they do not have signs or symptoms of the disease, as it does not improve survival but may expose women unnecessarily to surgical complications. This is the final guidance from the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), published online February 13 in JAMA.

In a grade D recommendation against the use of ovarian screening, the USPSTF says that current tests do not accurately identify whether a woman does or does not have ovarian cancer.

A false positive result may lead to a woman’s undergoing surgery to remove one or both ovaries without her having the disease.

The recommendation does not apply to women who are at high risk of developing ovarian cancer, such as those carrying BRCA gene mutations.

This final statement on ovarian cancer screening confirms a draft version of the guidelines released in July 2017, as reported by Medscape Medical News. The recommendation against routine screening also echoes recommendations of previous guidelines published in 2012 and 2004, all of which found that the potential harms of ovarian cancer screening outweighed the potential benefits.

The “evidence shows that current screening methods do not prevent women from dying of ovarian cancer, and that screening can lead to unnecessary surgery in women without cancer,” USPSTF member Michael J. Barry, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, commented in a statement.

USPSTF member Michael J. Barry, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, said in a release that the “evidence shows that current screening methods do not prevent women from dying of ovarian cancer and that screening can lead to unnecessary surgery in women without cancer.”

Coauthor Chien-Wen Tseng, MD, MPH, Hawaii Medical Service Association Endowed Chair in Health Services and Quality Research, who is also on the task force, called for research to find better screening methods to “help reduce the number of women who die from ovarian cancer.”

“Ovarian cancer is a devastating disease, and we do not have a good way to identify women with ovarian cancer early enough to treat it effectively,” she added.

Stephanie V. Blank, MD, professor of gynecologic oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who was not involved in developing the recommendations, agreed that there is a lack of effective tests for the disease.

“In the general population, ovarian cancer is a relatively rare disease, and the specificity of our current tests is not acceptable,” she said in a statement. “False positives in ovarian cancer screening can result in unindicated surgeries.

However, in a related editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine, Steven A. Narod, MD, Women’s College Research Institute, Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, Canada, argues that “we should not give up entirely on ovarian cancer screening.”

He points to recent research showing that the majority of high-grade serous ovarian cancers originate in the fallopian tube and that striving to identify cancers in stages I and II is based on the false assumption that the cancer stage is the main predictor of survival.

Narod concludes: “Screening for ovarian cancer is not ready for prime time, but there are reasons why we should continue the quest.”

In an JAMA editorial, Karen H. Lu, MD, Department of Gynecologic Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, echoes the call for more effective screening strategies, but also urges the development of complementary prevention programs.

She writes: “Broadening the strategy to include accurate risk models and genetic testing, novel prevention options, and effective early detection may help reduce the incidence and high mortality associated with ovarian cancer.”

In an editorial in JAMA Oncology, Charles W. Drescher, MD, and Garnet L. Anderson, PhD, Public Health Sciences Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, write that the incremental improvement of screening performance could result in meaningful benefits not yet seen in the trial data.

“Better risk-prediction tools could lead to more targeted screening and a higher likelihood of an overall benefit, even with current screening modalities,” they write. “Additional biomarkers, particularly those that are not dependent on tumor burden, may provide better screening performance and potentially at an earlier, more treatable stage.

“Imaging technology that can reliably detect tumors as small as a few millimeters in size and localized to the fallopian tubes would also likely contribute,” they add.

To read this entire article in The Clearity Portal, please click here.