Lawsuits didn’t do it, public shaming didn’t do it, patients and doctors banding together to “free the data” couldn’t do it: For 22 years Myriad Genetics, one of the oldest genetic testing companies, has refused to make public its proprietary database of BRCA1 variants, which lists more than 17,000 known misspellings in that major “cancer risk” gene, along with the medical significance of each. The database lists which mutations increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, which do not, and which have an unknown health effect.

But now a blitzkrieg of biology has hacked the secret cache of life-and-death data.

By deliberately causing every possible mutation of the kind that occurs most commonly in BRCA1, and tracking how cells growing in lab dishes respond, scientists at the University of Washington determined which mutations are pathogenic and which are benign, they reported on Wednesday in the journal Nature. They also made that call for more than 2,000 variants whose health consequences have been unknown, a breakthrough that promises to spare thousands of women the anxiety of not knowing if their BRCA1 variant is a ticking time bomb or nothing to worry about.

Calling the research “provocative,” Dr. Stephen Chanock of the National Cancer Institute, an expert on cancer genes, said in an essay accompanying the paper that it “should turn heads.”

The researchers have made their list of variant calls publicly available. They urge physicians and genetic counselors to use the results to inform patient care, including advising women who test positive for a risk-raising BRCA1 variant to consider steps such as mastectomy and oophorectomy, as Angelina Jolie famously chose, or telling those whose variant is innocuous that they can breathe easier.

“We’re bullish about using this data clinically,” said geneticist Jay Shendure of the Brotman Baty Institute for Precision Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, co-leader of the study. “If it were my relative” deciding what to do after learning she has a BRCA1 mutation whose meaning has been unclear up to now, he said, “I would be comfortable using this to tip the balance.”

About 12 percent of women will develop breast cancer, but 72 percent of those who inherit a harmful BRCA1 mutation will. Just over 1 percent of women will develop ovarian cancer, but 44 percent with a harmful BRCA1 mutation will. But because there are many genetic and environmental causes of cancer, BRCA1 mutations account for only 5 to 10 percent of breast cancer diagnoses overall and 15 percent of ovarian cancers.

Information on the meaning of BRCA1 variants has been known for the most common ones and for variants whose cancer-causing abilities are unambiguous. It can be found in publicly available BRCA databases such as ClinVar, run by the National Institutes of Health, whose data come from individual researchers, testing labs that compete with Myriad, and other sources.

For 2,345 “variants of unknown significance” in ClinVar, as well as very rare BRCA1 variants, however, thousands of women have been left in a quandary. Should they gamble that their puzzling variant is benign and go about their lives, or have life-altering surgery just to be safe?

Myriad has the largest and, it says, best source of what-does-it-mean information. But it is available only to women who get its $3,000 BRCA test, not any of the less expensive BRCA tests that have been commercially available since the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated Myriad’s gene patents in 2013.

For hundreds of variants, however, Myriad doesn’t know the cancer-risk significance either. With the new data, said Lea Starita of the Brotman Baty, who co-led the study, “we can move 90 percent” of the variants of unknown significance in public databases “one way or the other,” deeming them pathogenic or benign. “For rare variants, this might be the only data that’s out there.”

Myriad declined a request for comment. It passed 1 million BRCA tests in 2013.

BRCA expert Dr. Heidi Rehm of Harvard Medical School said clinicians could use the data from the Washington group now, calling their approach “well validated.” In almost every case, the new data agree with existing data on whether a BRCA1 variant is benign or deleterious. When it delivers new information, classifying a previously puzzling variant as one or the other, she said, clinicians “should weight that” in advising patients.

The NCI’s Chanock was more cautious. “It might be tempting to make immediate use” of the information to interpret puzzling variants found when women undergo BRCA tests, he wrote, but it “should not be used as the basis for medical advice — at least until the approach has been clinically validated.”

That’s the gold standard for variant interpretation: whether women with a specific variant developed cancer or not. “But there isn’t a lot of that clinical data, or it’s in a silo held by Myriad,” Starita said.

She and her colleagues therefore aimed to figure out the consequences of BRCA1 variants by marching through the gene like General Sherman through Georgia.

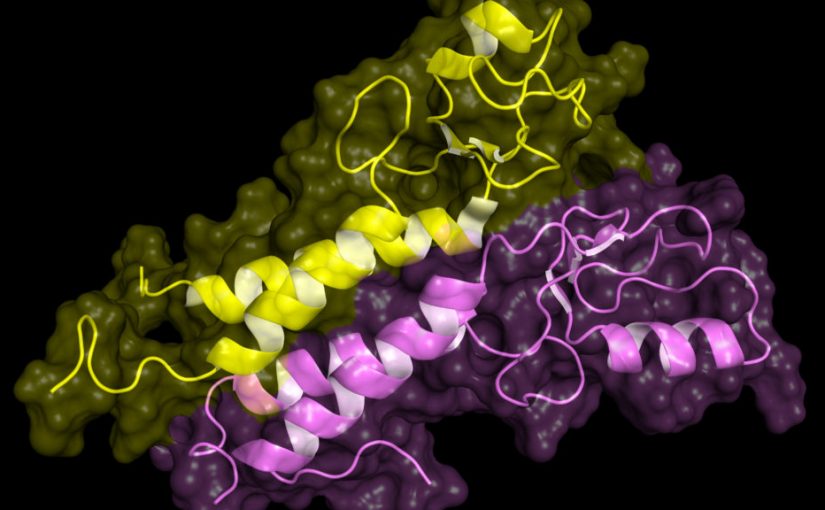

The gene makes a large, ribbon-like protein, also called BRCA1. The protein repairs broken DNA, but only two pieces of the ribbon, made by several hundred nucleotides (the chemical “letters” A,T, C, and G), really matter. Using a standard cell line, the scientists therefore changed one letter at a time in these pieces to any of the three alternatives (say, changing an A to T, C, or G), for a total of 3,893 variants, in cells from a lab workhorse called HAP1. They called their approach, which used the DNA editor CRISPR to make those single letter changes, “saturation genome editing.”

In each experiment, they edited one region of the BRCA1 genes in 20 million cells simultaneously and let the cells grow in lab dishes for 11 days. They then measured the effects of each single-letter change to see which ones killed the cells. That was an indication that the BRCA1 repair protein was impaired. In people, when that happens, DNA damage goes unaddressed and cancer can develop.

Result: Every one of the 3,893 variants in the BRCA1 could be interpreted as harming the BRCA1 protein and therefore leaving a cell vulnerable to cancer, or not.

About 72 percent of single-letter variants had no deleterious effect on the BRCA1 protein; those wouldn’t cause breast or ovarian cancer, a result that agreed with existing data. One-fifth of the single-letter variants harmed the protein enough to impair its DNA-repairing ability and so increase the risk of cancer; that, too, agreed with ClinVar data.

Shendure, Starita, and their team are now using the same approach on BRCA2, a related gene whose variants can also cause breast and ovarian cancer.

This article was published by STAT.