By: Annette McElhiney

As a devoted reader of the The New York Times, I find some peace (beside the national news and editorials) that captures my attention and imagination. Recently, they were both jolted by the piece, “I Used to Insist I Didn’t Get Angry. Not Anymore.” by Leslie Jamison.

As a 9.5 year ovarian cancer survivor and advocate, I frequently interact with other cancer patients who have just been diagnosed or are recurring. We often share the feelings we have had that people who don’t have cancer simply don’t understand. Two feelings most of us had, or still have, are profound sadness and anger. Most people expect and respect our sadness but our anger, not so much. So after reading this article, I began questioning the value of these emotions in a cancer survivor’s fight for survival.

Leslie Jamison writes, “The phenomenon of female anger has often been turned against itself, the figure of the angry woman reframed as threat — not the one who has been harmed, but the one bent on harming. She conjures a lineage of threatening archetypes: the harpy and her talons, the witch and her spells, the medusa and her writhing locks. The notion that female anger is unnatural or destructive is learned young; children report perceiving displays of anger as more acceptable from boys than from girls. According to a review of studies of gender and anger written in 2000 by Ann M. Kring, a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, men and women self-report “anger episodes” with comparable degrees of frequency, but women report experiencing more shame and embarrassment in their aftermath. People are more likely to use words like “bitchy” and “hostile” to describe female anger, while male anger is more likely to be described as “strong.”

When I got my diagnosis of IIIC ovarian cancer in 2008, I was sad and as were my family and friends. Crying was to be expected and we did plenty of that. What I didn’t feel comfortable expressing was the rage I felt at being dealt such a blow when I’d done everything I could to prevent it. From the time I was 20, I always had annual pelvic exams, I had my first child at 23, I breast fed my children, and I never took post menopausal hormones. Those were all deliberate acts that the textbooks of the time said should have protected me from ovarian cancer. What went wrong? I couldn’t stop thinking about other women who hadn’t done any of these things but still didn’t have cancer. Frankly, I felt I’d gotten a raw deal.

Because I didn’t want to be perceived as “feeling sorry for myself,” I stuffed my anger and became stoic. Yet in my head I was still angry and stoicism took its own toll.

Every ovarian cancer patient or survivor learns early that if she wants to survive, she will have to formulate a plan to get herself through the after effects of surgery and chemotherapy.

Even though Jamison wasn’t talking about the anger that comes with cancer, she came to the same conclusion. She writes, “Confronting my own aversion to anger asked me to shift from seeing it simply as an emotion to be felt, and toward understanding it as a tool to be used: part of a well-stocked arsenal.” I also had to put my anger in my tool belt, to use it to energize my healing and to help me move forward.

Within 24 hours after my surgery, I asked my surgeon about my prognosis. He said I had a 25% to 35%chance of living 5 years. I was terrified, but at the same time I resisted his prediction. In my head, I kept thinking, “how dare he measure my life in such negative terms!” I determined that I’d be my own statistic! So without ever really realizing I was doing it, I set out to prove my doctor wrong.

My chemotherapy sessions were in my surgeon’s office and I chose a station where he would have to see me every time he went in and out of an examination room. Somehow, instinctively, I knew that in order to stoke my anger, I needed a constant reminder of my resolution to prove him wrong.

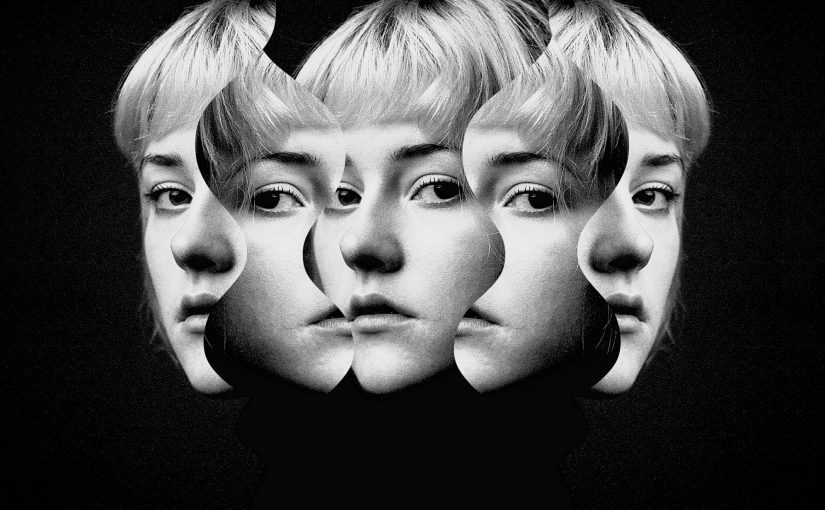

After I completed 8 sessions of chemotherapy, I had to find another outlet to keep my anger alive and fueling my recovery. I was too embarrassed to complain or admit my anger out loud, I had to find an acceptable way to express it. As an amateur painter and writer, I found throwing paint on a canvas helped. Eventually, I created a character (an alter ego of sorts), Althea — who could express my anger in a way I couldn’t. She was brash, confrontational, and uninhibited. When asked how I felt I’d always politely say “I’m fine.” Not Althea. Instead she’d say “I feel like HELL so just stay out of my way!”

While this strategy may not be for everyone, it worked for me as I used my anger as an energizing tool for recovery.

Jamison eloquently describes how to use anger as a source when she writes, “Once upon a time/I had enough anger in me to crack crystal’ the poet Kiki Petrosino writes in her 2011 poem ‘At the Teahouse.” I boiled up from bed/in my enormous nightdress, with my lungs full of burning/chrysanthemums.’ This is a vision of anger as fuel and fire, as a powerful inoculation against passivity, as strange but holy milk suckled from the wolf. This anger is more like an itch than a wound. It demands that something happen.”

I have been extremely fortunate because my cancer has not recurred. The further away I get from diagnosis, the more I draw upon my anger to propel my advocacy for other ovarian cancers survivors. I’m angry about a disease that affects the lives of so many women, both young and old, in every country and from every race. I’m also angry that ovarian cancer, as a woman’s disease only, is given far less research money than those diseases that affect both men and women.

My mother always said, “the squeaky wheel gets the grease.” So perhaps it’s time women use their anger as fuel to convert the high mortality rate of ovarian cancer patients to a much lower one. I am and will continue to be “a squeaky wheel” and I hope you will join me.